273rd Infantry Regiment

Steadily Advance

History of the 273rd Infantry Regiment

Authored by Elbert H. Duncan and able assistants

Edited by Michael T. McKibben, Website Engineer

A copy of Steadily Advance as printed and issued to the 273rd Infantry Regiment in Germany in 1945 is no longer available. This 273rd unit history includes writing and pictures about the our time in Colditz which was not written previously. A spiral-bound copy of this additional history is available from the webmaster.

For more information, contact: annejoelip@bellsouth.net

Col. Charles M. Adams

Regimental Commander

273rd Infantry Regiment

Dedications

To all the officers and men of the 273rd, I send my sincere congratulations on a job well done. You have fought gloriously against one powerful foe and have laid him prostrate at your feet. Ever mindful of the battle achievements herein recorded, let us steadily advance toward the complete and final victory.

|

|

Our Colleagues: To all the officers and men of the 273rd, I send my sincere congratulations on a job well done. You have fought gloriously against one powerful foe and have laid him prostrate at your feet. Ever mindful of the battle achievements herein recorded, let us steadily advance toward the complete and final victory. It is with admiration and grateful thanks that we salute our fighting colleagues. Till we meet again! |

Introduction

The men of the 273rd Infantry received their first glimpse of Europe from the decks of their transports early one Sunday morning, as the Cornish coast of southwest England appeared on the horizon. It came as welcome relief after two weeks on the North Atlantic in what could hardly be termed luxurious accommodations. After docking at Avonmouth and Southampton, and an all-night train ride, the Regiment was quartered in the quaint and attractive vicinity of Winchester, in the inevitable Nissen huts that dotted all of England.

Despite the urgent priority of equipment and supply, and a regular training schedule initiated soon after arrival, passes were given freely, allowing the men to visit the nearby towns of Andover, Basingstoke and Winchester. A system of special trains to London was instituted to allow the maximum number possible to enjoy two 40-hour passes to London during the two months' stay in the United Kingdom.

At the turn of the New Year, a grave and astounding situation had arisen. The Germans had kept their promise. Led by Rundstedt, the German armies had pushed back into Belgium and had reached their climax early in January. Casualties had run high; whole units with all their equipment had been lost, while all Allied winter plans were seriously impaired. Morale had been dealt a terrible jolt. It was now apparent that the time for the Regiment's Channel crossing was approaching… Conflict was inevitable.

Finally, on January 22, 1945, the troops moved by train to the port of Southampton. On the afternoon of the same day, they embarked for their trip to the Continent. The Regiment (less Headquarters and Headquarters Company) boarded the British transport Morowai, while Headquarters and Headquarters Company made the channel crossing aboard an LST (Landing Ship, Tank).

As if prophetic of the days to come, winter unleashed all its fury as the Regiment disembarked in the harbor of Le Havre, France, on the night of January 23rd. A raging snowstorm beat upon the decks of the Morowai as she dropped anchor some distance off shore in the late afternoon. By this time, the snow had changed into a driving, icy rain, which lashed at the faces of some 2,500 "Doughs" as they poured down the chutes onto the slippery LCIs (landing craft, infantry) standing alongside the ship to ferry the troops ashore.

Pouring onto the beaches from the barges, men trudged along with their burdensome duffel bags and full field packs. The 80-mile all-night ride in open vans that followed will not soon be forgotten by the men of the 273rd. Though packed closely in the back of the huge trucks, little comfort could be gained by huddling even closer to one another, and in the excruciating cold, disgruntled voices garbled vaguely about frostbite and trench foot. It was not until 0700 the following morning that the vehicles arrived in Forges Les Eaux, after having traveled by the way of Rouen. Here, the advance detachments guided the Battalions to their billets, all of which were located in and around Gournay en Bray, the site of the Regimental Headquarters.

During the one-week stop here, little training was scheduled, all efforts being concentrated on keeping warm and checking the equipment for another jaunt across France. On January 31st, the foot troops moved by "forty and eight" boxcars to Sissone, where for seven days, the men slogged in ankle-deep mud and lived in a "tent city" that had been hastily put together only a few hours before their arrival. Throughout the week, the weather was quite dismal, and the first thaws turned the entire countryside into a quagmire. With the exception of one or two movies and a shower at the portable Quartermaster bathing unit, there was little to encourage the Regiment on the eve of battle.

Ready to advance

On the morning of February 8th, 1945, a move by "forty and eight" boxcars through northeastern France and southern Belgium brought the troops of the 273d Infantry Regiment to Heppenbach in the St. Vith and Malmedy areas. Orders were received on the morning of February 10th that the Regiment would move into the line within 48 hours to relieve the 393d Infantry of the 99th Infantry Division.

The Regimental Commander, Battalion Commanders and staff went forward on the afternoon of February 10th to inspect the 393rd's position and to arrange for the relieving of that regiment from the lines near Udenbreth, Germany. Returning the same day, the Regimental Commander issued orders for the move, from his Command Post at Heppenbach.

In the gloom of the rainy morning of February 12th, all elements of the regiment began moving over the snow-covered ground of the Bullingen Forest area, near Udenbreth. Before the following dawn, all of the 393rd's positions were taken by the combat-green troops of the 273rd.

From their twig-covered dugouts, curious "Doughs" peered across the Siegfried's dragon-teeth formations into the mysterious land of the enemy over which they were to march in triumph all the way to the Elbe, where the historic meeting with the Russians took place.

In the Siegfried Line – And Out

Eleven o'clock, Monday, February 12, 1945! And the green doughboys of the 273rd Infantry Regiment moved into the Siegfried Line for their baptism of fire. The day was dreary, marked by low-hanging clouds, as the men replaced the battle-weary GIs of the 393d Infantry Regiment, 99th Division. Sensing the change in combat troops, the Jerries threw everything they had at the 273rd "Doughs." With the scent of battle in their nostrils, the men of the Regiment accepted the challenge to fight, and promised to "Steadily Advance" under any and all conditions.

Upon taking up positions on the line, the regiment sent out combat and reconnaissance patrols. For 14 days, from February 13 to February 27, these teams infiltrated the enemy lines, getting as much information as possible about the German defenses that stood between our front lines and the Rhine River. It was imperative that these defenses be taken, and Colonel Adams' men accomplished their mission successfully. The patrols encountered stiff opposition in the form of heavily mined fields, harassing sniper fire, continual machine gun fire, and mortar barrages. The Jerries also sent over rocket barrages, screaming meemies, and their famous 88 shells. The men took everything thrown at them, and were now ready to return blow for blow.

It was the 27th of February, and the Second Battalion lashed out with the first big attack, securing a bridgehead across the Prether River and seizing Giescheid. The First Battalion attacked at daylight of the 28th and secured Bamberg. The Second Battalion then seized Rescheid, while the Third Battalion seized pillboxes 82 and 83, and high ground southwest of Schnorrenberg on March 1. By 2400 of the 28th of February, the First Battalion had also secured Hill 648 and high ground in the outskirts of Schnorrenberg. The occupation of Schnorrenberg was completed by noon of March 1.

The time had come for the Regiment to be relieved by the 272d. However, there was no rest to be had for Colonel Adams' hard-fighting men. Instead, the Regiment relieved the 110th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Division and set up positions in the vicinity of Hellenthal, Blumenthal, and Schoneseiffen. On the fifth of March, elements of the Second and Third Battalions captured and occupied Oberhausen, Blumenthal, and pillboxes in the vicinity. The First Battalion captured Renenberg on the 7th of March, and Wildenberg, Menscheid, and Zingscheid on the 8th of March. The Regiment then assembled at Hecken on the night of March 8, and was pinched out by the 2d Division and 271st Infantry Regiment.

The initial drive toward the Rhine River and the heart of Germany was completed, 25 days after their first taste of battle. Flushed with victory and morale high, the men settled down to a hard-earned rest, and eagerly looked forward over the hills to the Rhine River, only a few miles away.

Across the Rhine

By mid-March, the regiment, along with the rest of the division, had broken through the Siegfried defenses and was hurtling toward the Rhine. The Ninth Armored had established the spectacular Remagen bridgehead into which huge numbers of men and immense quantities of supplies were pouring. Tense units awaited their turn to span the famous waterway which represented the last natural barrier between the onrushing Americans and the heart of Germany.

On March 26, the First Battalion of the 273d joined the First and Second Battalions of the 272nd to form a Combat Team which was to spearhead the drive across the Rhine. Troops of Lt. Col. "Wild Bill" Salladin, then a major, were brought to a point on the west bank of the river just south of Remagen. Here they were treated to doughnuts and coffee from the familiar Red Cross Clubmobile as they waited for assault boats which were to ferry them across. As searchlights played along the Rhine's eastern bank and machine guns spoke through the steady artillery, the foot troops stepped aboard the LCIs. Simultaneously, under blackout, the motor convoy crept north to cross the Victory Bridge, then, suddenly turning, slashed many miles south and reorganized at Bendorf.

By nightfall, the entire battalion was on the east bank, and on the 27th of March, the remainder of the regiment made the historic crossing.

Fort Ehrenbreitstein

Off again before dawn, the First Battalion "Doughs" under the command of Lt. Col. W. D. Salladin were started on their historic capture of Fort Ehrenbreitstein and Fort Neiderberg.

The plan for taking Fort Ehrenbreitstein was issued in the early morning hours of March 27, and by dawn, the companies began their trek toward the hilltop garrison. In a pincer movement that threatened to encircle the enemy troops lodged in the fortress, the Combat Team forced the surrender of the proud bastion and took over 150 prisoners.

On Army Day, April 6, speaking at Fort Ehrenbreitstein, General Bradley paid tribute to the "Fighting 69th" while an honor guard from the Division raised the Stars and Strips over the fallen garrison.

Hann. Münden

And thus the wave of battle swept through the smaller countryside towns and villages of Central Germany. Germany's rich industrial areas and vast agricultural regions were falling into our grasping hands, and now was her opportune moment for a great stand. Aided by excellent defense terrain consisting of high mountains, deep sloping valleys which were watered by winding, twisting currents, and defended by fanatically entrenched SS troops including veteran Wehrmacht goose steppers, her last great stand was to be made in the vicinity of Hann. Münden.

On the night of April 5, under the complete cover of darkness, the Second Battalion, ably commanded by Lt. Col. John M. Lynch, initiated the drive toward the heavily defended city of Hann. Münden. The order of the day for the Third Battalion was to secure a bridgehead across the Fulda River and move to Lutterberg, while the First followed closely in reserve.

Carrying out their mission, the Second Battalion pushed northwest of the Fulda River against heavy opposition, reaching high ground west of Hann. Münden, encountering an enemy of 1,000, reinforced by heavy machine guns, 80 mm and 120 mm mortars. Moving forward, elements of the battalion on the morning of the 6th made the crossing of the Fulda River at Wilhelmshausen and advanced on Bonnafort. By early nightfall, the remainder of the battalion crossed the river and secured Bonnafort. During this time, the Second called on the Division Artillery to shell Hann. Münden. The order was now given to Second Battalion to seize the Werra River bridge.

All armor and organic transportation was moved across a bridge at Kassel to give full support to the advancing Third Battalion, moving slowly on account of roadblocks. Part of the Third crossed the Fulda River in the early morning, and the remainder made the crossing in the afternoon. As they approached Lutterberg, fierce resistance was encountered. There was increasingly heavy machine gun, mortar, 88, self-propelled, and small arms fire. The first attack at 1310 was held up by heavy fire, but a second coordinated attack was successful, and by 2046, the town was taken. To assist in completing the regimental mission, the battalion was divided into two columns supported by armor. The columns were to seize crossings on the Werra River in the vicinity of Hedemunden, and to hold high ground east of the river. The river was crossed in assault boats, and the Third advanced on Hedemunden, completing their mission.

The First Battalion was now ordered to follow the Third across the foot bridge at Speele and take over the Second Battalion's mission. The move started at 0730, the 6th of April, and the bridge was reached at 1230. While awaiting the fall of Lutterberg, the battalion crossed the Fulda at Kassel. Later in the evening, the Battalion engaged in a heavy fight, killing approximately 40 enemy, and in the early morning of the 7th had advanced along the Autobahn with leading elements in Laubach. The new mission of the First was to seize high ground east of the Werra River. A reconnaissance of the Werra River was completed in the vicinity of Laubach, but the enemy had complete observation and was placing artillery and mortar fire at the located bridge crossing. Orders were then received to make a 180-degree turn where the towns of Lippoldshausen and Wiershausen were cleared. Receiving heavy fire from northeast of Hann. Münden, and against stiff opposition, the Battalion gained its objective.

The Second Battalion entered Hann. Münden proper at 1500 the 7th of April, and seized the town at 2049. The town was cleared on the 8th, and the Second became attached to Combat Command A while the Third, upon completion of their mission, assembled at Hedemunden and was assigned to Combat Command R. The First Battalion moved to Mollenfelde and joined the 273d Combat Team.

Altengroitzsch

Leaving Hedemunden, the Third Battalion, as part of Combat Command R, moved to Gertenbach, where they pushed eastward. The objective this time was Altengroitzsch, a heavily defended town lying in the road to Leipzig.

Little activity was encountered until the third day, when they were greeted by air bursts from 88s. The infantry immediately detrucked and proceeded to attack high ground overlooking their positions in which were located observation posts that were calling fire upon the column.

The observation posts were wiped out, and the battalion moved into town, destroying 27 leveled 88s. On the 14th of April, Altengroitzsch was mopped up, leaving one less obstacle in the path of the regiment prior to its participation in the battle for Leipzig.

Colditz-Mulde

Orders were received for Third Battalion to continue their drive and remove the one remaining obstacle in the path of the regiment. Defensive positions would be established to the south and east of Leipzig to prevent reinforcements. As part of the battalion moved on the town, they were halted by sniper and machine gun fire. The companies immediately formed a skirmish line and advanced with marching fire, encountering resistance from well dug-in enemy positions. The remaining elements of the battalion moved into Colditz, but due to heavy fire withdrew, and during the night, artillery was placed on the town.

13th April 1945

The Battalion took part in the battle near Altenroitsch – outer defense belt of Leipzig. In the 13-hour battle, Company L lost 11 killed, 11 wounded.

In Colditz arrived the last vestiges of an unidentified WaffenSS Division with about 800 troops. It immediately prepared to defend the hills east of the castle. behind the infantry regiment already in town. The SS soldiers brought with them truckloads of the tank-busting Panzerfausts, which they distributed among the Volkssturm. They also had a few 88mm anti-aircraft guns, which were deployed along the ridge above the castle.

Sometime during the following 72 hours, the SS troops went to the HASAG concentration camp south of Colditz. There they murdered 400 Hungarian Jews who were being used as slave laborers. Four of the Jews managed to survive by crawling under the bodies of the dead.

View Larger Map |

Figure: 1 – April 15, 1945 battle route of the 273rd Infantry Regiment. (A) Wildenhain, (B) Breitingen, (C) Blumroda, (D) Wyhra, (E) Schoenau, (F) Elbisbach, (G) Hopfgarten, (F) Ebersbach and (G) Hohnbach |

14th April 1945

The 3rd Battalion was ordered to move to Wildenhain, south of Borna.

15th April 1945

9:00 (look at Eggers, 14:00 look at Narveson)

10:00

The Battalion moved out of Wildenhain (see Figure 1), passed through Breitingen, Blumroda, Wyhra, Schoenau, Elbisbach, and Hopfgarten, and reached Ebersbach and Hohnbach at 14:00.

The Sunday was clear and sunny. Five American tanks came out of the woods to the west and advanced on Honbach. They set fire to a couple of houses without reply, Suddenly a shell hit the guardroom close to the main gate of the castle.

One shell hit Wing Commander Bader's window, on the third floor of the Saalhaus - a French man was wounded. No one killed yet.

The next shot skimmed the north-west corner of the castle, crashing over the pagoda and through the tree branches.

Broken fire from a howitzer continued throughout the morning and one of the sergeants was killed near the bridge outside the castle. Two shots hit the Kommandantur building, but that was all the damage the staff suffered, because the prisoners put a French flag up on the roof, which stopped the gunner.

The Americans had known, that there are prisoners of war in Colditz, but not where. They thought, behind the walls of the Castle German tanks were hidden.

10:30 (look at Narveson)

The prisoners spotted tanks due west of town; but as the tanks approached they were recognized as German. Thunderbolts dive-bombed the tanks. The tanks moved into the protection of Colditz's narrow streets and crossed the town bridge.

|

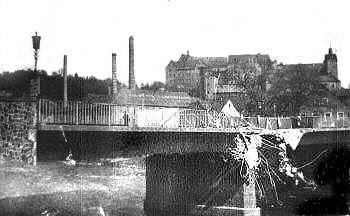

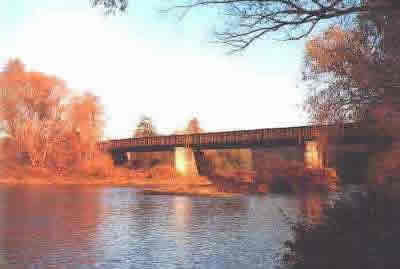

Figure 2 – Volkssturm ans WaffenSS detonated WWI vintage ammunition under this Colditz bridge three days earlier, then detonated it on April 15, 1945. After the bridge did not fail, the WaffenSS troops blasted the center piling with Panzerfausts for an hour, but failed to destroy the bridge. |

14:00

There was a tremendous explosion as Volkssturm ans WaffenSS detonated the ammunition dated from WWI, placed under the bridge three days before. But the bridge remained standing. The soldiers began blasting the center piling of the bridge with Panzerfausts for about an hour. But they must have left more than half the central piling still intact.

|

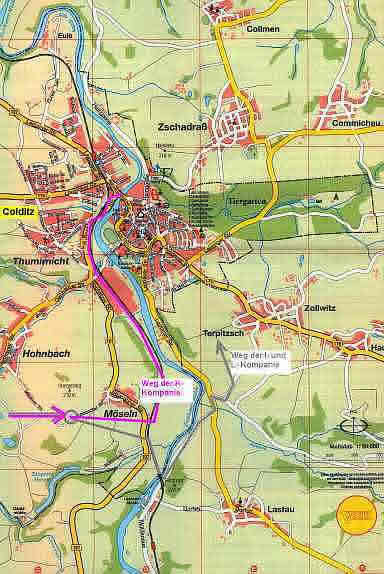

Figure 3: Map of Colditz, Germany and vicinity. The Mulde River flows through the town. |

16:00

The Battalion received from CCR Hq at Schoenbach the order to take Colditz.

From a departure point at Hohnbach (may be the hill Hungerberg) I Company was to move south-east, cross the Mulde River on the railroad bridge which had been taken intact, and then was to attack Colditz from the south. After crossing the railroad bridge they turned left walking along the river bank to the street to Terpitzsch and headed up the hill between Terpitzsch and home tower to take there position.

K Company was to attack the part of Colditz on the west bank of the river, and l Company was to follow K. Self-propelled artillery of 9th Armored Division was in position to give supporting fire, and there was also fire on call from the tanks and TDs attached to the Battalion.

|

|

Figure 4 – 273rd Inf Reg I Company was to move south-east, cross the Mulde River on the railroad bridge which had been taken intact, and then was to attack Colditz from the south. |

19:00

The companies were in position to launch the attack and artillery preparation was laid down.

From the start, I company had a rough time. All the resistance proved to be on the east side of the river, and that part of Colditz was by far the greater part of Colditz. I company was hardly across their Line of Departure when they were met by heavy machine-gun and rifle fire. Panzerfausts were used also by the Germans in the close-in fighting that developed. After the first attempt of attack the company had to withdraw behind the hill.

The railroad bridge, over which they had crossed, was now under fire by the Germans. German soldiers were seen heading over towards the vicinity of this bridge and river bank. Evidently they were trying to get around and encircle the company.

All the assistance possible in form of artillery fire was given to I company but as darkness fell it became evident that the eastern portion of Colditz could not be cleared that night.

In the night the company made another attack against the town making it into the outskirts and occupied some buildings, but the Germans forced them out. Some of the GIs were cut off from the rest of the company. Germans walked among the wounded lay there, to finish them off.

Four men, including two platoon sergeants, had been killed; 8 men had been wounded. One of the killed sergeants, Sgt. Hadaway, 26 years old. He was very respected as a fine human comrade by his GIs, who were in their teens.

|

| Figure 6 – Meanwhile K and L Company encountered little difficulty clearing that part of Colditz on the west bank of the river. Under small arms fire from the high ground across the river they moved up the railroad tracks and in the ditches of the railroad. |

Meanwhile K and L Company encountered little difficulty clearing that part of Colditz on the west bank of the river. Under small arms fire from the high ground across the river they moved up the railroad tracks and in the ditches of the railroad. When they reached the HASAG factory a mortar observer positioned himself there. He didn't remember seeing any Hungarian PW's, but didn't explore the factory. Mortar fire was directed to the factory on the Leisniger street.

When the company approached the bridge between the two parts of the town, resistance was met. In an attempt to check the bridge, Sergeant Miskovic was killed and another man was wounded. The German guards on the bridge were also killed.

|

Figure 5 – The railroad bridge, over which they had crossed, was now under fire by the Germans. German soldiers were seen heading over towards the vicinity of this bridge and river bank. Evidently they were trying to get around and encircle the company...After crossing the railroad bridge they [273rd Inf Div I Company] turned left walking along the river bank to the street to Terpitzsch and headed up the hill between Terpitzsch and home tower to take there position. |

L Company was withdrawn to Hohnbach the day before. were they got orders for an attack with I Company at daybreak.

During the dark hours of morning, L Company crossed the railroad bridge that I Company had used and moved abreast of I Company.

But an attack was not necessary that bright Monday morning. The Germans had withdrawn. A few prisoners were taken.

The marketplace was filled with US troops, news and motion-picture photographers.

The freed prisoners began the celebration that lasted far into the night.

L Company moved out of Colditz to prepare defenses in Zschadrass (a village nearby) and I Company moved out to Hausdorf. K Company remained west of the Mulde river. M Company and Hq Company set up in Colditz proper. The castle became the Bn CP.

The Battalion remained in place, chiefly concerned with patrol activity and the evacuation of the prisoners until 19th April.

Colonel Shaughnessey wrote later:"The 'Battle' of Colditz was certainly not a major military operation. The phase of the war, the diminishing potential of the German Army, and the impending link-up of the American and Russian forces made the actual capture of the city a rather commonplace action. It is true that the initial attack did meet frenzied last-ditch resistance. Also, a defended Colditz Castle would indeed have been formidable to take by ground attack without a long siege. The most significant factor in the liberation of Colditz prison was the fact that the prisoners themselves, alert to the situation, had, in reality, captured the prison from within and had full control of everything necessary to deliver it to us. The event of the next few days, particularly the return to freedom of several hundred outstanding military men held captive by Nazi Germany for many month, made the capture of Colditz a noteworthy humanitarian triumph rather than a military episode." |

16th April 1945

The attack continued on April 16, with the battalion moving into the town virtually unopposed, SS cadre having withdrawn during the night, and at 1100 seized the town. Many prisoners were taken, and thousands of Allied prisoners of war were liberated from Colditz Castle. Third Battalion, successfully led by Lt. Col. Leo W. Shaughnessy, completed its mission of providing flank security for troops attacking Leipzig.

The Battle for Leipzig

The conquest of Leipzig, Germany's fifth city, was the climax to the combat operations of the 273d Infantry. The regiment had been among the forward spearhead elements of the First Army in their drive from the Rhine eastward into the heart of Nazi Germany ... now Leipzig, manufacturing and cultural center of the Reich, was within reach of the American forces, and the Nazis were determined not to allow this rich prize to fall without a bitter struggle.

On April 17, the 273d Combat Team, with the support of attached armored and tank destroyer units, received the order to advance on Leipzig, assuming the sector previously held by the 271st. Early the following morning the regiment, with its attached units, reached an assembly point at Lieberwolkwitz. Here the battalions were given separate missions for the attack on the city proper. One company was detached to "Task Force Zebra," which was composed, except for this company, of tanks and tank destroyers. This task force moved directly into the city riding on the armored vehicles, and despite strong opposition, had reached the City Hall by early evening. Meanwhile, the First and Second Battalions were advancing in their respective sectors. The First Battalion was encountering stiff resistance on the road toward Holzhausen, while the Second Battalion had advanced into Leipzig and was engaged in fighting near the Sports Palace against well dug-in and defended enemy positions.

By 2000, the Second Battalion was fighting against heavy opposition around the monument of the Battle of Nations. This monument was to prove the hardest single Nazi installation to take in the battle for Leipzig. Dedicated in 1913 as a memorial to Napoleonic Wars 100 years before, its fantastic symbolism represented, to the easily impressed German mind, everything from the eternal glory of the Reich to the everlasting impregnability of Germany's borders. The monument itself is a massive affair, topped off with giant figures representing the Nazi war gods, and enormous statues representing ever-watchful soldiers guaranteeing that never again would hostile forces enter and fight upon the "Holy Soil" of Germany. In this monument, the embattled Germans, with a force estimated at several hundred storm troopers, made their final stand. When the initial assault of the regiment's Second Battalion was made upon it, resistance was so fierce that it was bypassed and submitted to a constant artillery barrage.

By midnight, the First and Second Battalions had fulfilled their missions within the city, and reorganization was effected in order to capture the City Hall, previous assaults having been unsuccessful. Under full attack, the City Hall surrendered early the second morning, and inside, men of the 273d found a strange sight. The mayor, his family, and high city officials had taken their own lives rather than to surrender to the advancing Americans.

Shortly after noon, all resistance in Leipzig had ceased, except for the still well-defended force in the monument. All efforts to take the stronghold having been repulsed during the afternoon, surrender negotiations were attempted. The fanatical Nazis still inside refused, although evacuation of wounded was effected. And as night wore on, it was decided to leave a guard outside and abandon all attempts to seize the monument, inasmuch as orders to move to the east had been received. But at 0200 on April 20th, the German commander agreed to surrender his force to save further bloodshed. The Battle of Leipzig had ended.

Thus had the fifth city if Germany fallen to the Americans. The name of Leipzig had long been famed as a manufacturing center, as well as the seat of most of pre-war Germany's cultural activities. In addition to numerous art galleries, museums, and concert halls, Leipzig was also the site of one of Europe's oldest and most famed universities prior to the dedication of the entire nation by the Nazis to the bloody road to war and ultimate destruction.

As the regiment moved out of Leipzig by motor on the morning of the 20th, little remained of the once-proud city. American air and ground forces had combined to reduce most of the city to little more than rubble, another milestone on the victorious American march through Germany toward and final meeting with Russian forces advancing from the east.

East Meets West

With the conquest of Leipzig completed, the regiment moved out to take up defensive positions along the Mulde River. Excitement ran high as rumors of a possible meeting with the oncoming Russians spread throughout the area. Patrols were constantly crossing the Mulde in hopes of making contact, while positions were established across the river from Trebsen to hold the only remaining bridge, all others having been blown by the retreating Germans.

For several days, there was little activity outside of patrolling, for reports had placed the Red Army troops so near the regiment's lines that orders were issued to fire only when the targets were unmistakably German. Another indication of their proximity was the steady stream of German prisoners who, in their efforts to escape capture by the Russians, used whatever means they could to reach American lines and even swam the Mulde at Wurzen to surrender to our forces.

Meanwhile, restless patrols were probing along the Elbe River in their eagerness to be the first to establish a union between the two great armies.

Finally, on the afternoon of 25 April, a patrol of 11 men led by Lt. Albert L. Kotzebue made the historic contact at Leckwitz near the Elbe River. Later in the day, two other groups unknown to each other, one led by Lt. William D. Robertson and the other by Major Fred W. Craig, made two separate contacts at approximately 1600 and 1645.

Patrol #1 |

Patrol #2 |

Patrol #3 |

|

|

|

Figure 7 – Kotzebue Patrol No. 1 – 1130 hours on April 25, 1945 – The 273rd Infantry Regiment’s 1st Lt. Albert L Kotzebue’s Patrol is recognized as the first Allied soldiers to meet the Russians at Leckwitz, Germany at 1130 hour on April 25, 1945. His patrol consisted of a total of 36 men from Hq Co, Med Det, Cos E, G and H 273 Inf Rgt. How these men were selected was never recorded. There is no known photo of the entire patrol. Picture here from left to right are Lt. Kotzebue, Houston, Texas, Co G; Medic Cpl. Stephen A. Kowalski, Med Det, New York, NY; Pfc. Byron L. Shiver Sr., Co H, Lancaster, SC and Pfc. Edward P. Huff, Co H, Riverside, NJ. Lt. Kozebue was the first American officer to shake hands with a Soviet officer. It took place near Strehla, Germany. Source: http://www.69th-infantry-division.com/images/Kotzebue-Patrol-No-1.jpg |

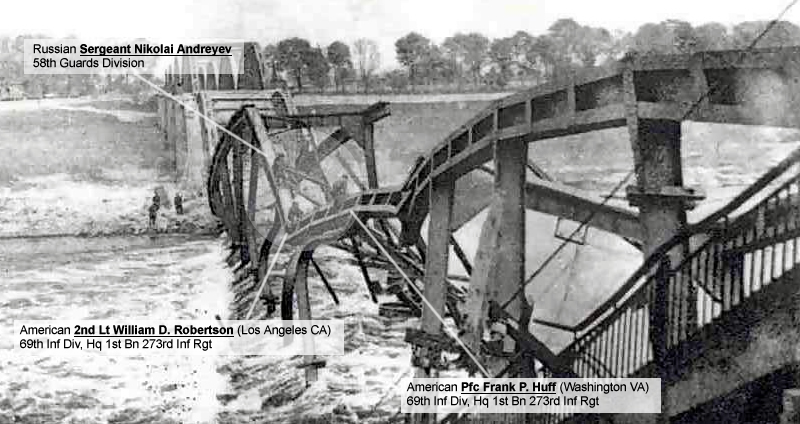

Figure 8 – Robertson Patrol No. 2 – 1600 hours on April 25, 1945 – 2nd. Lt. William D. Robertson, S-2, Hq Co 1st Bn 273rd Ind Rgt, was the leader of the second patrol to meet the Russians, Torgau, Germany at 1600 hours on April 25, 1945. He led a four man patrol consisting of from left to right: Pfc. Frank B Huff, Washington, VA; Cpl. James J. McDonnell, Peabody, MA; 2nd. Lt. William D. Robertson, Los Angeles, CA and Pfc. Paul Staub, The Bronx, NY, all from Hq Co 1st Bn 273rd Inf Rgt. The meeting took place with Robertson crawling onto the blasted Torgau Elbe River bridge to shake hands with Russian Sergeant Nickolay Andreyev who was a member of a Soviet patrol led by Lt. Alexander Silvashko. Source: http://www.69th-infantry-division.com/images/Robertson-Patrol-No-2.jpg |

Figure 9 – Craig Patrol No. 3 – 1645 hours on April 25, 1945 – The third patrol from the 69th Infantry Division’s 273rd Infantry Regiment to linkup with Russians soldiers was led by Major Fred W. Craig, Friendship, TN, Executive Officer (second in command) of the 2nd Battalion 273rd. Major Craig’s patrol consisted of 51 including Captain William J Fox, Hq V Corps, Brooklyn, NY and Pfc.William Seiter, Detroit, MI, Hq 1st Army. The others came from Hq and Companys E, G and H 273rd Inf Rgt. The patrol met its first Russian soldier at Clanzschwitz, Germany at 1645 hours on April 25, 1945. Pictured from left to right are Pfc. Igor N. Belousovitch, Co E, San Francisco, CA (extreme left). He was Major Craig’s Russian interpreter. Next is Major Fred W. Craig at the side of the horse. The other Russian and American soldiers pictured are unknown. In the next few days following this linkup Captain Fox interviewed the three patrol leaders and certain commanders and wrote a report of what took place called “The Fox Report.” Ironically, the opening session of the United Nations Conference to preserve world unity after the war occured the same day as the linkup on April 25, 1945. Source: http://www.69th-infantry-division.com/images/Craig-Patrol-No-3.jpg |

Perhaps the most colorful of the three meetings was Lt. Robertson's patrol.

He had learned from German prisoners that the Russians were across the Elbe at Torgau, a small historic town. After encountering small pockets which offered slight resistance, the patrol reached Torgau early in the afternoon. Realizing they had nothing to use for recognition purposes, the patrol stopped at a nearby drugstore, where a crude American flag was improvised from a piece of white cloth. A church steeple was sighted in the distance to where the men advanced, climbed the winding stairs and raised their flag. No sooner had the Russians seen the flag, when they shot a red flare in the air, as it had been understood that red and green flares would be used for signals when the two armies were near enough to make contact. Lt. Robertson being unable to answer with a green flare, the Russians immediately fired at the flag, believing it to be another German trick. Fortunately, no one was injured, and remembering a concentration camp they had liberated on the outskirts of Torgau, the patrol returned, telling their situation to a Soviet prisoner who readily rode back to the bank of the Elbe River, and yelling across, convinced his countrymen that the Americans were attempting to make contact. Further persuasion was not necessary, and without hesitation, both parties were on their way, scrambling over the girders of the blown bridge, to exchange greetings.

East meets West, Torgau Bridge, April 25, 1945, 16:00 |

|

| Figure 10: Russian 58th Guards Division and American 69th Infantry Division 273rd Infantry Regiment link up on 25-April-1945 at 16:00 hours and thus break the German forces in half at the blasted Torgau, Germany Elbe River Bridge on April 25, 1945. VE Day (Victory in Europe) followed rapidly on May 8, 1945. Source: http://www.69th-infantry-division.com/photogallery.html |

Thus had the two great Allies in the war against Nazism met and severed the enemy in two. And although the German Army, like the proverbial snake that wriggles until sundown, fought on for a few days more, its doom was sealed on the Elbe by the juncture of Russian forces with the men of the 273d.

For the Russians, it was the climax of long years of fighting, up from the heroic days of Stalingrad, the furthest point of German advance. It was a consummation of all the fighting through bitter winters and across burnt plains that had characterized the Russian struggle against Germany since 1941. It marked the end of a victorious advance that had included the capture of Berlin a few days earlier.

To the Americans, it marked the end of a victorious march lasting just under 11 months from the landings on the Normandy peninsula. It was a fitting climax to an effort that began in the winter of 1942 on the shores of North Africa. It was the junction for which the anti-Nazi world had been waiting since first the Germans loosed their armies on the freedom-loving countries of Europe.

For the men of the 273d, it marked the final victory in a series that had started with the initial assaults upon the Siegfried Line in the dead of winter. It was a fitting climax to a campaign which had carried them out of Belgium and into Germany itself with the breaching of the famed "Westwall," across the Rhine and the fertile valley beyond it, through the very heart of Germany itself, and had included, just a week before, the victorious storming and seizure of Leipzig.

Wurzen — Prison Town

After taking positions at the Mulde River in the town of Bennewitz, the First and Third Battalions of the regiment began to observe the actions of large enemy concentrations in the town of Wurzen, just across the river. Motives of these forces became clear on April 24, when the first of thousands to come began streaming across the river by any and every possible means to surrender and escape the approaching Soviets. For days the parade continued. That complete disorganization had taken place was obvious. The officers commanded no respect from the men, and seemed not to care. The all-consuming desire was to surrender, and in this they were speedily accommodated.

It was hard to believe that the same men who marched so docilely were the ones who such a short time ago reduced most of Europe to slavery and had become synonymous with savagery and destruction. No sympathy was given these "Supermen" in this, their final degradation.

Excerpted from 273d Infantry: Steadily Advance, p. 4-16.